Why Ergonomic Chairs Still Cause Back Pain

Ergonomic seating is often presented as the answer to modern workplace discomfort. The idea is straightforward. A chair designed around the human body should reduce strain, support posture, and help prevent back pain. Yet many people who invest in ergonomic chairs continue to experience discomfort in the lower back, mid back, or hips. From our perspective as a furniture brand focused on real world use, this disconnect rarely comes down to a single design flaw. It usually comes from how ergonomics is understood, applied, and relied upon.

Back pain persists not because ergonomic chairs are ineffective, but because chairs are often expected to solve problems that extend beyond the chair itself. Understanding why this happens requires looking at how seating interacts with anatomy, movement, and the surrounding work environment.

The Promise and Misinterpretation of Ergonomic Seating

Ergonomic design is rooted in human factors research. Its purpose is to reduce unnecessary strain by aligning furniture with how the body naturally functions. In seating, this means supporting the spine, distributing weight evenly, and minimizing joint stress. The challenge is that these goals are often simplified or misunderstood once they reach everyday use.

Many people browse office chair collections for workspaces expecting a chair alone to resolve years of discomfort. When pain continues, frustration follows. In most cases, the chair has not failed. The expectation placed on it was simply too narrow.

How Ergonomic Became a Catch All Label

Over time, ergonomic became a broad marketing term rather than a precise description. Chairs with very different designs, levels of adjustability, and intended use are grouped under the same label. This creates confusion about what ergonomic seating can realistically accomplish.

True ergonomic design accounts for posture variability, movement, and long term use. When the label is applied too loosely, it sets expectations that no single chair can meet.

Comfort Versus Structural Support

Comfort and support are not the same thing. A chair can feel comfortable at first while quietly placing strain on the lower back or hips. Soft cushioning may reduce pressure initially but can also allow the pelvis to sink unevenly, altering spinal alignment over time. Discomfort often develops gradually rather than immediately.

Design Intent Versus Daily Use

Even a thoughtfully designed chair depends on how it is used. Sitting habits, task demands, and desk setup all influence whether ergonomic features help or hinder the body. Design can guide posture, but it cannot replace healthy movement or awareness.

Lumbar Support That Misses the Mark

Lumbar support is often seen as the defining feature of an ergonomic chair. While lower back support is important, it is also one of the most misunderstood elements of seating.

Fixed Curvature and Forced Spinal Extension

Many chairs use a fixed or pronounced lumbar curve intended to maintain the natural inward curve of the spine. For some users, this feels supportive. For others, it pushes the lower back into excessive extension. This increases compression in the lumbar discs and can lead to muscle tension and fatigue.

Vertical Placement and Torso Proportion

The position of lumbar support matters as much as its shape. If the support sits too high or too low relative to the user’s anatomy, it can miss the lumbar region entirely. Differences in torso length and pelvic orientation make universal placement difficult.

When evaluating seating such as the ergonomic Novo chair product page, it becomes clear that lumbar support works best when considered as one component within a broader seating system.

Pelvic Orientation and Spinal Geometry

The pelvis acts as the base of the spine. Small variations in pelvic tilt influence how the lumbar curve forms naturally. Chairs that impose a specific curve may conflict with this natural variation, especially during long sitting sessions.

Seat Pan Design as a Hidden Driver of Back Pain

While lumbar support receives the most attention, the seat pan often has a greater impact on long term comfort and spinal health.

Seat Depth and Backrest Engagement

Seat depth determines whether a user can sit fully back against the backrest without pressure behind the knees. If the seat is too deep, users slide forward, losing contact with the backrest and increasing strain on the lower back. If it is too shallow, weight distribution becomes uneven.

Cushion Compression and Pelvic Stability

Cushion firmness influences how the pelvis is supported. Very soft foam can compress unevenly over time, allowing the pelvis to tilt backward. Very firm surfaces can create pressure points that encourage slouching or constant repositioning.

The Muse chair product overview reflects a seating approach where seat form and materials are designed to balance comfort and pelvic support, though individual response still varies.

The Relationship Between Pelvis and Lumbar Load

When the pelvis tilts, the lumbar spine follows. This is why seat pan design often plays a larger role in back comfort than lumbar support alone.

Why Static Good Posture Still Leads to Pain

One of the most persistent misconceptions about ergonomics is the idea of a single correct posture that should be maintained all day. In practice, static posture is a major contributor to discomfort.

Sustained Muscle Activation

Holding the body in one position requires continuous muscle engagement. Over time, this reduces circulation and increases fatigue, even if the posture appears neutral. Muscles are designed for movement, not prolonged holding.

The Need for Micro Movement

Healthy sitting involves frequent, subtle changes in position. These micro movements redistribute pressure, promote blood flow, and reduce localized strain. Chairs that allow gentle shifting tend to support comfort better throughout the day.

Designs highlighted on the ergonomic Onyx chair listing illustrate how seating can encourage natural movement rather than rigid positioning.

Neutral Is Not Permanent

Neutral alignment serves as a reference point, not a posture meant to be held continuously. Effective ergonomics supports movement between positions.

Armrests and Backrests That Alter Spinal Load

Upper body support features influence lower back comfort more than many people realize.

Armrest Height and Shoulder Tension

Armrests set too high elevate the shoulders, increasing tension in the neck and upper back. This tension travels down the spine, altering lower back loading. Armrests set too low offer little support and often encourage slouching.

Backrest Resistance and Movement

Backrests that resist movement or lock easily can discourage natural recline. When the backrest does not move with the body, users tend to lean forward, increasing lumbar strain.

The Seashell chair product details demonstrate how backrest form can support the upper body without restricting subtle motion.

Upper Body Support and Lumbar Interaction

The spine functions as a connected structure. Changes in shoulder or upper back support inevitably influence the lower back.

When the Chair Is Right but the Desk Is Wrong

Back pain is often blamed on the chair when the surrounding setup is the real issue.

Desk Height and Forward Lean

If a desk is too high or too low, users compensate by leaning forward or raising the shoulders. This shifts the spine out of alignment and increases lumbar flexion over time.

The Chair Desk Monitor Relationship

Chair height, desk height, and monitor placement form a single system. Adjusting one element without considering the others often creates new sources of strain.

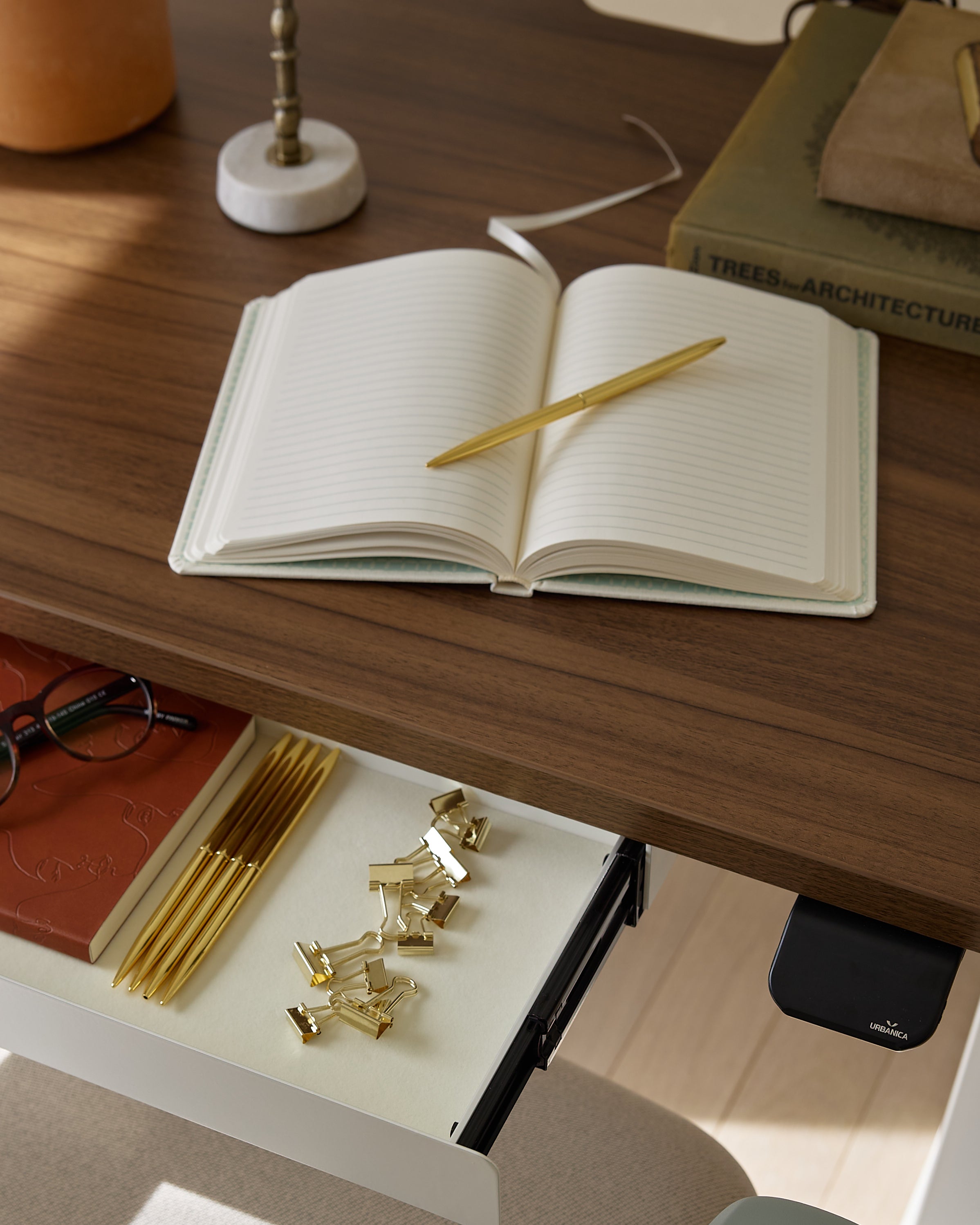

Pairing seating with appropriate work desks for office environments helps align this system and reduce compensatory posture.

Why Chairs Depend on Their Environment

A chair does not operate in isolation. Its effectiveness depends on how well it integrates with the surrounding workspace.

Individual Body Variables Chairs Cannot Automatically Solve

Human bodies differ in ways that no single chair can fully accommodate.

Body Weight and Material Response

Cushions and supports respond differently depending on load. A chair that feels supportive to one person may feel overly firm or too soft to another, even when adjusted properly.

Height, Leg Length, and Proportion

Seat height, depth, and backrest placement interact with leg length and torso height. Mismatches here often lead to subtle posture changes that accumulate into discomfort.

Task Based Sitting Behavior

Different types of work place different demands on seating.

-

Extended screen work increases static load

-

Task switching introduces frequent posture changes

-

Creative work often involves leaning, turning, or perching

Each pattern interacts with chair design in a different way.

Why Chairs Are Blamed for What Sedentary Behavior Causes

Many discomfort issues attributed to chairs are actually driven by prolonged sitting itself.

Reduced Movement as a Core Risk Factor

Extended sitting reduces muscle activity, joint lubrication, and circulation. Even a well designed chair cannot fully counteract the effects of limited movement over long periods.

What Chairs Can and Cannot Do

| Chair Capability | What It Helps With | What It Cannot Prevent |

|---|---|---|

| Lumbar shaping | Reduces localized pressure | Effects of prolonged immobility |

| Adjustable components | Improves fit | Muscle fatigue from static posture |

| Supportive materials | Enhances comfort | Reduced movement throughout the day |

Understanding these limits helps set realistic expectations.

Evaluating Ergonomic Chairs With a More Honest Lens

Choosing seating becomes more effective when approached as part of a broader system.

What Matters Beyond the Label

Adjustment range, material response, and how a chair behaves during movement often matter more than how it is described. Seating should support a range of postures rather than enforce a single one.

Real World Testing Over Short Trials

Short sitting tests rarely reveal how a chair performs over hours of use. Experiencing seating in a realistic environment provides better insight into long term support. Visiting a physical showroom for office furniture allows for this type of evaluation without relying on assumptions.

Reframing Ergonomics as a System, Not a Product

Back pain persists when ergonomics is treated as a purchase instead of a practice. Chairs play an important role, but they function best alongside appropriate desks, thoughtful layout, and regular movement. From our perspective, effective ergonomics supports the body as it works, shifts, and adapts throughout the day. When seating is selected and used within this larger system, it becomes a tool for support rather than a promise of relief.

Leave a comment